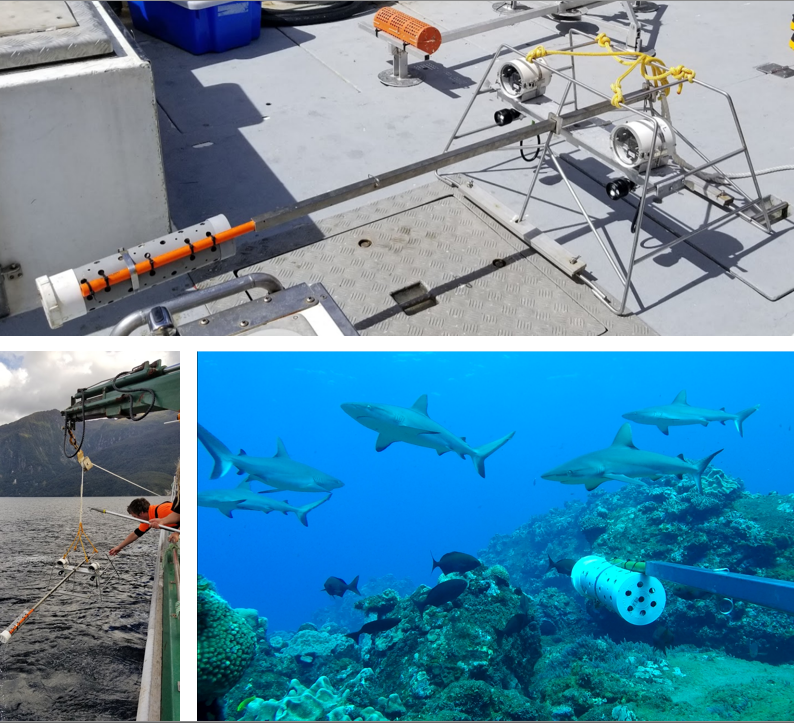

The BRUV method

Stereo Baited Remote Underwater Video (BRUV or SBRUV) is a way of surveying fish and habitats. A BRUV unit has a container of bait that attracts fish, and these fish are recorded by video cameras aimed at the bait. During a survey, we deploy our six BRUV units from a boat to the sea floor at predetermined sites, attaching them to a rope and buoy. Each BRUV is left to record for an hour before we retrieve it, swap the batteries, and redeploy—repeating the process multiple times per day. After the fieldwork, we systematically review the footage to extract biological data, usually in the form of counts and sizes of each species of fish, and observations of the habitat. Having two cameras in “stereo” allows us to accurately measure the lengths of fish, adding a key dimension to our data. With repeated surveys, we can track changes in fish communities over time.

The BRUV method has several advantages over other methods of sampling fish: it is efficient, standardised, non-destructive, and generally less species- and size-selective. The video footage becomes a permanent record of the habitat and biological community.

Sea Through Science has extensive experience conducting underwater surveys worldwide, from the Galapagos Islands1,2 to Fiordland, New Zealand. We’ve worked in diverse environments, including coral reefs in Fiji and Tonga, remote ecosystems like Rangitāhua/Kermadec Islands, and marine reserves in the Hauraki Gulf3,4.” Adam co-authored the guide to the BRUV method5 and publications in Nature6 and Science7 as part of the Global FinPrint project.

Footage from our BRUVs

We have plenty of videos on our YouTube channel, but some notable mentions are below.

Fiordland great white

One of our BRUVs caught a curious white shark in Fiordland in February 2025, making news in NZ and abroad.

Full article on RNZ.

Kermit the Kermadec Island great white

An expedition to the Southwest Pacific

A global study of shark populations

Newshub: Sharks ‘functionally extinct’ at many coral reefs around the world